I come from the dark side.

Between 1994 and 1999, I studied at two business schools. Then I worked in advertising and marketing from 1999 until 2016 — for 17 years. First I was an employee in a couple of advertising agencies. Then I got a doctorate in Marketing and helped build our own specialised agency, with a group of friends and colleagues. The one over-riding goal of everything was always:

Growth.

Advertisers may cite many reasons why they work with advertising and marketing agencies, but at the end of the day, they all want the same thing: to grow their market share, their profits, their sales.

And make no mistake: All advertising agencies ever want for themselves is growth, too. More clients. Bigger staff. More campaigns. More money.

Nobody who works in advertising ever questions any of this. There is no time. There is always the next deadline. The next flight to the meeting. The next crazy client request. The next ego emergency. Besides, why question the hand that feeds you? Growth pays for advertising. Then advertising begets more growth. Its a virtuously vicious circle.

I myself had no idea that something might be wrong. And when the news were reporting another year of GDP growth, it was the kind of good news I was happy to hear — I’d grown up in cold war “Economic Miracle” Germany, after all.

And yet, about a dozen years into my career it dawned on me that I could not, would not, should not spend the rest of my days trying to sell more of this shampoo or that floor cleaner. That that was simply not a worthwhile pursuit for a life well lived.

But I couldn’t leave right away, I had to stick it out for another four years, we had to keep growing our business so we could sell our company. I was fairly lucky with my contract and my role in the company — once the deal was done, I could quietly slip out the back door. The new owners hardly even realised that I was no longer there.

It was March 2016. I was in Munich.

I got an electric car — I thought that would be my contribution to protecting the climate. I went to Barcelona for a month, to spend time with friends. Then I moved back to Berlin. Brexit happened. It made me sad. I was living in a small apartment on Urbanstraße in Kreuzberg that I had rented from a friend. I was experimenting with a bit of freedom and with my underused creativity. In other news, the German right-wing party “AfD” was on the rise. I didn’t know what to do about it. Should I be more political? My father had been in politics.

I didn’t have a family of my own (I still don’t), I was alone. I made a hand-drawn animated short film. I reconnected with old friends. I thought about new professions I could take on. I felt a bit lonely. Autumn was coming. But overall, I was trusting that things would somehow be fine.

Then, Donald Trump got elected.

Many were shocked by the news, but ultimately this political earthquake did not leave much of an impact in the daily lives of many people in most European countries. Modern capitalism keeps us simply too busy to care: A presentation is due for the boss. There is the problems with the co-worker at the office. The neighbour just bought a new large SUV. Should we get one, too? One of the children is ill. Let’s just pray that the insurance will cover it. Also, the older one needs a new phone. The car has to go to the garage. A big SUV might feel safer, right? Oh my god, did we remember to book the flights for the holidays? Plus, can we even afford to put Ma in that retirement home? Oh man, health insurance rates went up again.

And so on. And then, at the dinner table, you might find a short moment, you’re looking at one another, saying: “Oh man, Trump is the American President now, that’s something else, isn’t it?” You shake your heads in disbelief, and then it’s back to the daily race.

Well, me … I had none of that.

I was by myself, no one needed me.

I was running nowhere.

No one waited for me.

I had no place to go, no job to do.

Instead, I was looking at the wall in that small apartment — and Trump was always there.

Soon I realised: This wasn’t about a complete catastrophe of a US President. It was about a very different question: What is going on in this world that the United States of America elect someone as horrific as him as “the leader of the free world”.

Where and when had things gone so badly wrong? What had I missed?

2017 became my fact-finding year. I read books and newspapers. I spoke with people. I launched a blog and wrote regularly about my experiences and questions. Soon, the climate crisis rose to the top of my agenda: jointly with my friend Kai Schächtele, I developed a show format called vollehalle — it talks about the climate emergency and the role of us all in it, in a constructive and inspiring manner. We also interviewed Tim Jackson for it. A giant among those who are imagining a better economy. Meeting Tim was my first brush with a new way of thinking about the system I had taken for granted.

And another thing happened to me in 2017: inspired by a small article in the German newspaper “taz”, I discovered the “Netzwerk Plurale Ökonomik” — the German arm of the “Rethinking Economics” student movement. Thanks in part to our meeting with Tim Jackson, and also to David Graeber’s book “Debt” and Wolfgang Streeck’s “Gekaufte Zeit” (English title: “Buying Time“), it was dawning on me that the way we are running and thinking about our economies is probably a big part of the problem. But so far, I hadn’t met anybody who had useful answers. So, I applied to attend the Netzwerk’s first Summer Academy, which took place at the beginning of August 2017 in the small village Neudietendorf outside Erfurt. And I got accepted.

That week in August of 2017 changed my life.

Never before had I seen 90 people — most of them millennial students — so heavily engaged in deep, thoughtful, intellectually curious and generous debate about the major issues of our time. They weren’t shouting their written-in-stone political beliefs or adherence to some political party at one another. Instead, these (mostly) twenty-somethings were soft-spoken and genuinely curious about each other’s thoughts, about how to advance their own thinking, in order to get to new solutions. And they were going at it non-stop, from 8 am at the breakfast table until 2 am at night, as they were having their nightcap beers in the courtyard.

It dawned on me: If there is hope for our world, it’s with critical economics thinkers like these students — with their radically open eyes and their real questions and their genuine curiosity.

And there was something else that I realised: Nobody knows this. Nobody outside these circles knows that the ideas that will solve many of our most dire problems may already exist. And they lie in truly rethinking our economy. In other words, nobody outside these circles seemed to realise that economics was the most important and most exciting subject of our time, if tackled in the right way. I understood that we needed to vehemently start telling these stories and bring this thinking to a wider world. The stories that I was hearing here, the thinking that was going on here, it needed to be shouted off rooftops!

And that was just the informal part of the week.

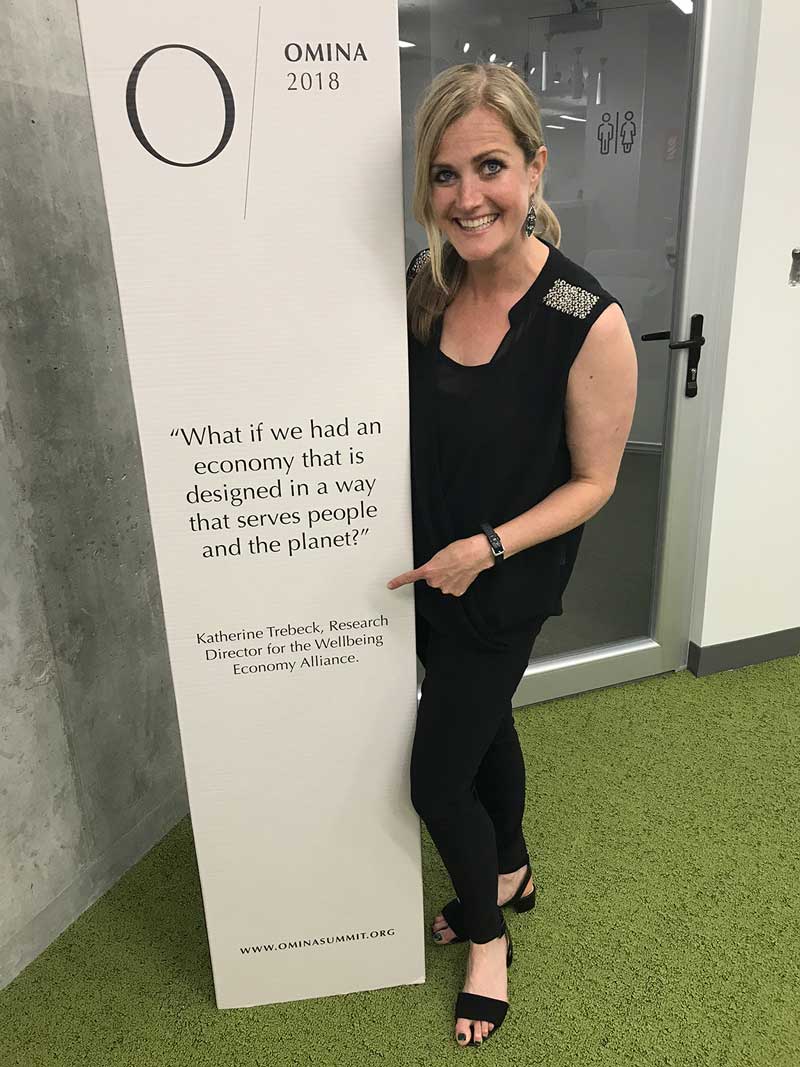

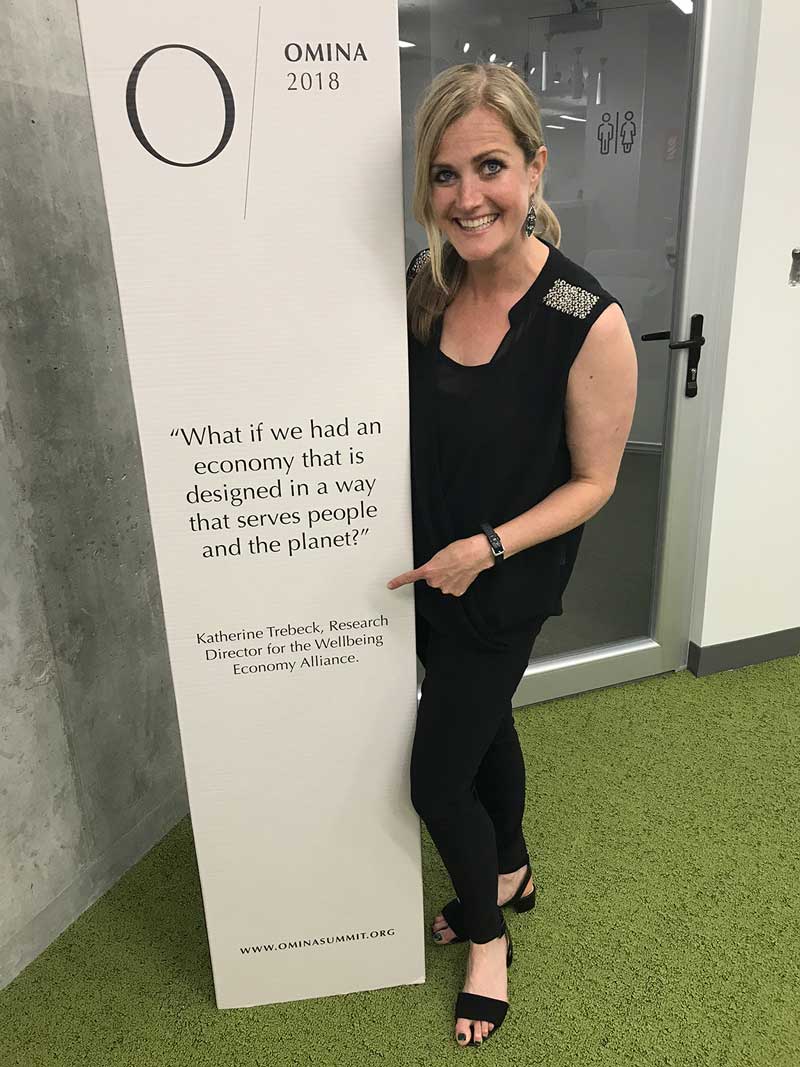

The biggest part of the official agenda were the workshops. The one I had signed up for was called “Prosperity Economics”, led by Katherine Trebeck and Himanshu Shekhar. At the time, Katherine was a researcher at Oxfam in Scotland. She explained to us how GDP was at best an imperfect measure of progress and how an alternative take on “prosperity” would look at the real issues. She also talked about the challenges of measuring prosperity holistically, in a way that deals with how people’s lives — and the lives of all other living beings on this earth, too! — are really going.

And then she told us about a plan she had, jointly with an Italian professor named Lorenzo Fioramonti who was teaching Political Economics in South Africa. They wanted to build a “counter-G7”: A new summit that would bring countries together who tell the world: “Enough is enough, let’s show the world how to think differently about the economy — in a way that can actually save mankind and this planet.”

They wanted to call it the “WE7”: the Wellbeing Economies 7.

What a story!

Six months later, I got a call from Gustav Theile. He’d been one of the Summer Academy organisers, now he was Katherine’s intern in Glasgow. He told me two things: One, the summit was happening! With Scotland, Costa Rica and Slovenia as the first members, getting together in Slovenia — there, they would jointly sign the Ljubiljana Declaration. And two, Lorenzo had left the project: He was returning to his native Italy, in order to run for office in the Italian election — he wanted to bring his post-GDP thinking into a new Italian Government.

I could not contain my excitement. So I turned to my friend Nick Scholey — a media creation one-man powerhouse, musician, camera operator, editor, all around creative force — and said, “Man, we gotta start making a documentary about this. Let’s go to Scotland and to Rome, let’s start filming these people. What they are doing is too important for the world to miss.”

We were now on a mission. And we got support from Kim Münster, a film producer.

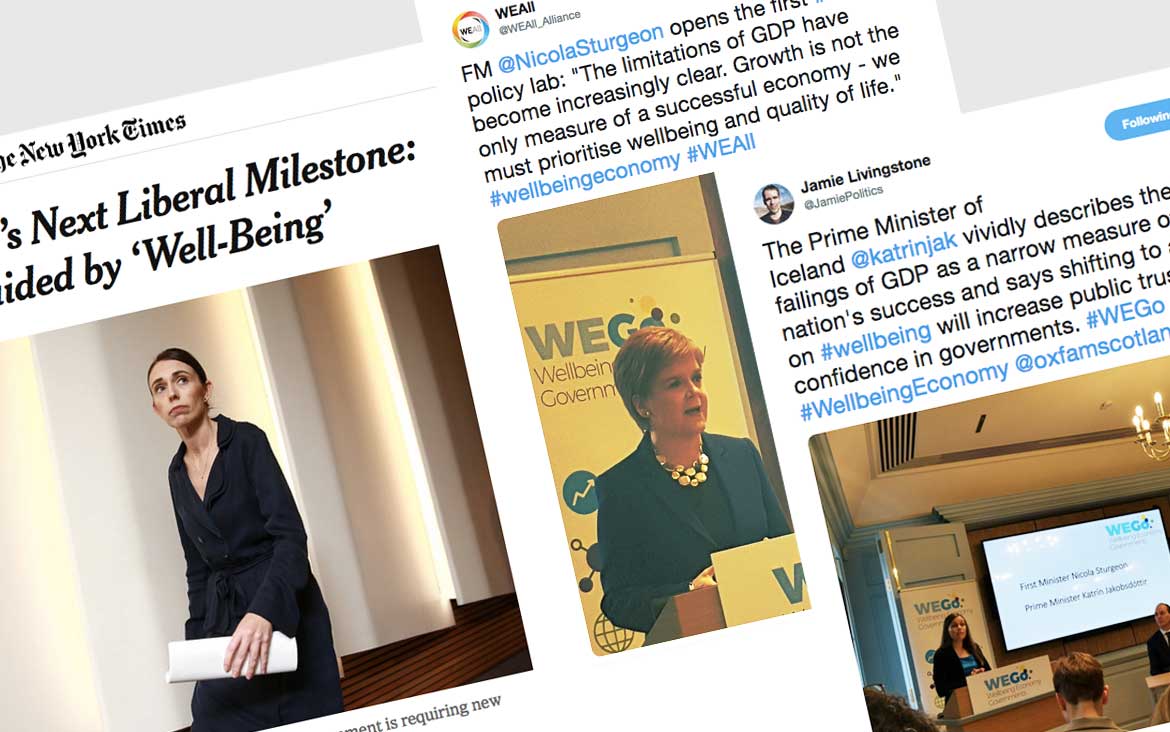

Today, one and a half years later, we have hours and hours of footage. Of Lorenzo’s political battles in that strange Five-Star-Lega government, which eventually fell apart — he’s now actually become the Minister for Education, in the brand new Italian Government. And of Katherine travelling around the world, helping save the Wellbeing Economies government project, after the summit in Ljubiljana got cancelled at the last minute. But Katherine and the amazing folks inside the Scottish Government kept at it. And so, a few weeks ago, Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, gave a TED Talk about how Scotland, Iceland and New Zealand had joined forces as the Wellbeing Economy Governments!

I am a very different person from the one I was in early 2016. I really hope that I will look back one day and say:

I made my way from the dark side to the light. And it wasn’t too late.

=======

This text was originally published a few weeks ago as a guest-piece on the Degrowth.info blog. We are cross-posting it here because it tells the background story of this film project.

You must be logged in to post a comment.